Edna St Vincent Millay: Poet, Radical, and Bohemian Icon.

When she wasn't writing poetry, Millay actively engaged in the radical politics of her time as well as the evolving mores and attitudes of her Bohemian peers before and after World War one.

I first encountered the poetry of Edna St. Vincent Millay during a high school literature class when I carelessly attached one of her poems to a poetry project I was rushing to finish before the deadline. As is typical at seventeen, I lacked the understanding necessary to realize that I had just stumbled upon not only a literary giant but also an individual who was part of a bohemian and fascinating era of history. It seems almost poetic (if I'm going to be discussing Millay, I can't help but use that word) that, four years later, I would randomly pick up a copy of Nancy Milford's Savage Beauty: The Life of Edna St. Vincent Millay from a bookstore off Murray Street in Greenwich Village—of all places.

Humble Origins:

Born on February 22, 1892, Millay was the eldest of three daughters. Her parents, Cora and Henry, separated in 1900. Henry would not be a part of Milays life after the split. She spent the rest of her youth growing up alongside her sisters Norma, Kathleen, and her mother in Maine and Newbury, Massachusetts. The family of four women often faced financial hardships. Millay's mother worked as a traveling nurse to provide for her daughters, leaving Millay to care for her sisters while she was away.

With the help of her mother’s encouragement, Millay began writing poetry at a young age, and her talent was quickly recognized. Her first published poem appeared in St. Nicholas Magazine in 1906, earning her the St. Nicholas gold badge for poetry at just fourteen. However, it wasn’t until her lyrical epic Renascence was published in 1912 that Millay gained the recognition she deserved as an emerging poetess. Renascence placed fourth in the Lyric Year competition published in 1912, and Millay received a scholarship from an impressed benefactor to receive an education from Vassar College, which she attended.

At Vassar, Milay was involved in numerous extracurriculars. Pagents, plays, and studying of the classics. Milay, like many college students, would begin exploring her sexuality by indulging in sapphic flings with her other female classmates (Vassar was a women’s only school until 1969.) Cementing herself as an early bisexual icon. Milay would write about one these flings in a journal entry labeled November 4, 1914; she writes… “She’s Elaine Ralli, a junior, another hockey hero, cheer-leader, rides horse-back a lot, very boyish, and makes a lot of noise, not tall, but all muscle”

After graduating, Millay moved into a nine-foot attic in New York City’s Greenwich Village, where she wrote anything an editor would accept. While this doesn’t sound like the most glamorous scenario, this environment, lifestyle, and the individuals she encountered shaped Millay into the poet and bohemian icon we remember her as today.

Bohemian & Radical Attitudes:

Edna arrived in the city during a significant time in history: 1917. The United States had just entered World War I, food riots were occurring throughout the city due to backlash against rising prices because of the war, and the New York City Women's Suffrage Party had just held its first successful campaign on Fifth Avenue. Millay was hitting her stride with her poetry; the August 1917 issue of Poetry magazine published three of her poems: "Kin to Sorrow," "A Little Tavern," and "Afternoon on a Hill." Ambitious as always, Millay began rubbing shoulders with some of the city’s elite aristocrats to secure theater roles alongside her writing.

Millay’s theater aspirations would come to fruition within a much different, yet more fitting, social sphere. She would encounter the Provincetown Players, a group of young artists, intellectuals, and radicals who produced experimental plays. In her biography, Milford writes…

“At an audition for the Provincetown Players in December, Edna Milay met Floyd Dell, who was casting his play The Angel Intrudes. He needed an ingenue, someone who was fresh and quick and bright, about whom it could be said, Anabelle is little. Anabelle’s petulant upturned lips are rosebud red. Anabelle’s eyes are baby blue. Anabelle is young. He waited impatiently one snowy afternoon at the tiny theater on Macdougal Street to listen to the young woman who had come to read for the part.”

Dell made Edna his ingenue and became her first serious romantic partner, introducing her to the world of left-wing politics and activism. Dell wrote for The Masses, a radical new magazine that the government had indicted under the Espionage Act. He and the magazine's editor and cartoonist faced up to twenty years of imprisonment.

The play opened on December 28th. Edna’s performance won over Dell and the rest of The Provincetown Player’s participants, and she was offered a spot in their troupe. The mix of influence from radical politics and the world of theater inspired Millay to try her hand at writing through a medium other than poetry. Millay wrote her first play, Aria Da Capo, in 1919. The play was produced by The Provincetown Players, of course, with Edna as the director and her sister Norma playing one of the leads. Aria Da Capo is a traditional Harlequin that cleverly addresses themes of the human condition and the cynical nature of war; for being her first playwright, it is tremendously impressive. Pierrot and Columbine's performance is interrupted by Cothurnus, who begins manipulating the action of the stage by pitting two shepherds against each other until the rivalry between the two becomes so heated they murder each other. Cothurnus buries their bodies under the stage, allowing Pierrot and Columbine to continue their performance, which he previously interrupted as if nothing had happened. This was Millay’s way of allegorically addressing and coming to terms with the monstrosities of World War I amongst a world that was so eager to move on and forget, encapsulating the essence of her generation (The Lost Generation, born 1883-1900.)

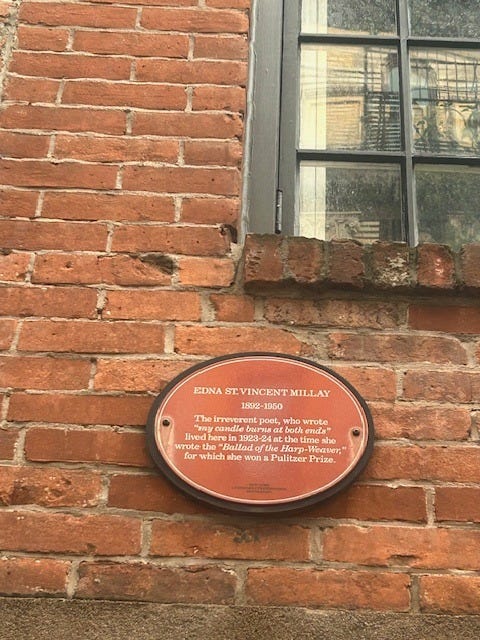

Milays time spent in Greenwich Village is permanently memorialized at the home she purchased on Bedford Street in 1923, which still exists today. A plaque inscribed by the front window reads Edna St. Vincent Milay 1892-1950 The irreverent poet, who wrote “my candle burns at both ends” lived here in 1923-24 at the time she wrote the “Ballad of the Harp-Weaver,” for which she won a Pulitzer Prize.

In the winter of 1921, Millay decided to try Paris; she was hired as an editor for Vanity Fair, receiving a regular salary. There, Milay would spend her time hanging out with (and having affairs with) Sculptors, Photographers, and journalists. The places she would frequent the most were two still popular cafes: Cafe de la Rotande and Cafe du Dome. This time spent in Paris inspired Millay to write the poem, which eventually won her the Pulitzer Prize, The Ballad Of The Harp- Weaver. However, the charm and excitement of Paris quickly died for Millay. Milford writes…

“If by the early 1920s Edna Millay had become a romantic figure— someone to make love to as a mark of one owns increased stature—- That June when Milay sat for a photograph by Man Ray, she looked desperately unhappy. Her face was drawn, her shoulders hunched; she was wrapped in a wooden shawl, hugging her arms across her stomach.” Milay was pregnant by a man named Daubingy. She secured a marriage license, but in a last-minute act of freedom, she fled Paris, returning to the New England countryside where her mother successfully induced an abortion with the use of the herb alkanet. However, this would leave Millay physically sick and weak on and off again for years.

In 1924, literary critic Harriet Monroe named Milay “The greatest women poet since Sappho.”

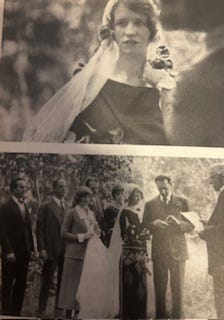

Millay married forty-three-year-old Eugene Jan Boissevan. Both radical for their time, they had an open marriage, each seeing numerous lovers. They would eventually move to Steepletop, their farm in Austerlitz, New York, where Boissevan, a self-proclaimed feminist, took on the domestic duties and chores, giving Milay the peace of mind and quiet to focus solely on her writing. It was the quiet pastoral lifestyle and aura of Steeple Top where Milay wrote her first opera, The Kings Henchman, which opened at The Metropolitan Oprea In New York City; Millay was exhilarated by this and felt she had reached her peak as a writer. Later in August of that year, despite her recent success , she stuck to her radical roots; Millay was arrested for protesting against the execution of two Italian-American anarchists.

End Of Life:

Milay would spend the rest of her life at Steepletop, traveling at various intervals. She continues writing. However, the complications from her previous abortion and a fall out of a moving car during the summer of 1936 left Millay in a considerable amount of pain. Both Milay and Boissevan would become addicted to morphine. Milford refers to their addiction and the way the entries they made to keep track of their drug usage as “The most pathetic journal entries in all of literary history.” However, Milay still managed to write when she could and even participated in a series of Sunday Night readings of her poems on the radio for NBC. She Received an honorary doctorate degree from NYU. Despite all this, she continued to grow weaker. Milay died of a heart attack in her home on October 19th, 1950, at the age of fifty-eight.

Edna St. Vincent Millay had published over seventeen poetry collections at the time of her death. In her obituary, the New York Times described her as “an idol of the younger generation during the glorious early days of Greenwich Village. And even more famously, Thomas Hardy referred to her by saying, “America had two great attractions, the skyscraper and Edna St. Vincent Millay.” I can’t think of a more fitting description. Milay was the progressive voice her generation needed to solidify their spot in history.

I’ve had ‘Savage Beauty’ on my TBR list for so, so long, and you’ve just officially inspired me to go and read it immediately! Really enjoyed this piece- thank you ❤️