A Writing Lesson From Virginia Woolf

Her Writing Technique

If you deem yourself a literary fanatic in any sense, then the name Virginia Woolf needs no introduction. But if you so happen to be someone pulled into this stream of consciousness of mine, then allow me some time to offer but a brief introduction. Literary fanatics and Woolf fans alike feel free to scroll past this introduction and dive straight into the writing techniques section of this article.

I can't first introduce Virginia Woolf and her writing techniques without first discussing the modernist literary movement, which originated in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Similarly to the Surrealist movement, it emerged in part as a coping mechanism and a reaction to the seeming absurdity and horrors of World War 1, industrialization, and urbanization. It signified both a departure from traditional ways of writing both poetry and prose, and a venture into a newer realm of writing which emphasized experimental forms and psychological depth. Woolf was one of the key pioneers of this modernist movement, implementing her signature style of Stream-of-Consciousness Writing.

Stream-Of-Conciousness Writing: A style of writing that seeks to mimic the natural, often chaotic movement of human thought rather than following a logical or structured order.

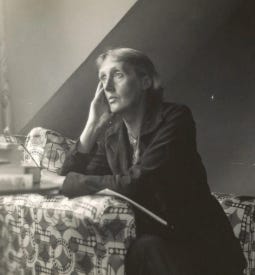

Virginia Woolf: A Brief History:

Woolf was born on the 25th of January 1882 in South Kensington, London, to an affluent and intellectual family. She grew up alongside eight siblings and spent her early years learning the English Classics and Victorian Literature. Her writing career began early in life. Woolf began by writing various diaries, letters, and short stories. She would go on to attend King’s College London, where she studied the classics and history.

Shortly after the death of her father in 1904, Woolf joined the Bloomsbury group, a literary circle of writers, artists, and thinkers who together challenged Victorian Social norms. This group both encouraged and inspired Woolf to pursue her writing career. She would also meet her eventual husband, Leonard Woolf, through this group.

Woolf published her first novel, The Voyage Out, in 1915, marking the begining of her career as a novelist. From 1915 until her death in 1941, she published nine novels. She also published numerous essays and articles, most of which expressed her feminist ideals and pacifist activism during the First World War. Woolf struggled with mental illness for most of her life and tragically took her own life at the age of fifty-nine.

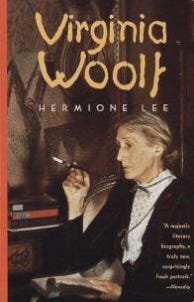

My brief introduction does this woman's incredible life no justice, but for the sake of this article, I intend to focus more on her writing technique than on her biography. For those more interested in learning more about Woolf’s life, family drama, political activism, and sapphic relationships, I redirect you to Virginia Woolf: A Biography by Hermione Lee.

The Writing Technique of Virginia Woolf:

Briefly, before I begin discussing Woolf’s writing techniques, take the time to read this opening paragraph from arguably her most popular novel, Mrs. Dalloway.

“What a lark! What a plunge! For so it had always seemed to her, when, with a little squeak of the hinges, which she could hear now, she had burst open the French windows and plunged at Bourton into the open air. How fresh, how calm, stiller than this of course, the air was in the early morning; like the flap of a wave; the kiss of a wave; chill and sharp and yet (for a girl of eighteen as she then was) solemn, feeling as she did, standing there at the open window, that something awful was about to happen; looking at the flowers, at the trees with the smoke winding off them and the rooks rising, falling; standing and looking until Peter Walsh said, “Musing among the vegetables?”--was that it?--”“ I prefer men to cauliflowers”--was that it? He must have said it at breakfast one morning when she had gone out on to the terrace--Peter Walsh. He would be back from India one of these days, June or July, she forgot which, for his letters were awfully dull; it was his sayings one remembered; his eyes, his pocket-knife, his smile, his grumpiness and, when millions of things had utterly vanished--how strange it was!--a few sayings like this about cabbages.”

If this is your first time reading this paragraph (if it's not, try to recall the first time you read it), did you notice it almost came across as strange? I remember the first time I tried to read Mrs. Dalloway about four years ago, I quickly put it down, bewildered by this style of writing I would eventually come to understand as stream-of-consciousness.

Stream-of-consciousness writing initially comes across as odd; our brains pause before registering it. It's different from the majority of writing we encounter throughout our lives, whether it's fiction or nonfiction. Most writing we expect to be structured and follow set grammatical rules. That's why it can be discouraging, initially, to read Woolf or to employ her style in our own writing.

This leads up to the first step of Virginia Woolf’s writing technique:

1. Let go of any limiting writing, rules, norms, and beliefs.

Those of us who journal understand that personal journaling often exceeds any limiting writing rules; it is a mode of writing that is not only personal but automatic and freeing. Woolf infuses her fiction with this, embracing the flow of thoughts, feelings, and sensations within all her characters. By doing so, she not only captures their inner lives but also shifts seamlessly between them, never limiting the narrative to just the protagonist's or the antagonist's points of view.

2. Prioritize Interior Monologue:

I’m currently writing my first novel, and one of the biggest frustrations I've encountered thus far is incorporating interpersonal interactions and external motivations into my protagonist’s character development. Traditional fiction expects this from authors, interpersonal interactions, and consistent external factors influencing the characters. Woolf defies this entirely, turning the traditional method inside out and instead allowing the interior monologue and inner lives of her characters to dictate the external circumstances of the story.

Woolf’s technique prioritizes Indirect Interior Monologue.

Indirect Interior Monolouge: A narrative technique that presents a character’s inner thoughts and feelings through the narrators voice rather than directly in the character’s own words.

This technique allows Woolf’s narration to shift seamlessly between characters’ minds without explicit markers such as “She thought” or quotation marks. Take, for example, this line from Mrs. Dalloway:

“Mrs. Dalloway said she would buy the flowers herself. For Lucy had her work cut out for her. The doors would be taken off their hinges; Rumpelmayer’s men were coming.”

The line “the doors Rumpelmayer’s men..” indicates a quick shift from narration into Ms. Dalloway’s private stream of thoughts.

When we prioritize interior monologue in our writing, as Woolf does, we prioritize subjective experience over external events, allowing external reality to be filtered through each character's perspective and creating multiple perspectives and blurred boundaries between narrator and character.

I like to think of it as turning traditional writing style inside out!

3. Time Is Meant To Be Fluid:

When we write, we often assume that time and events in our stories should be linear; it's human, after all, to want to record events in chronological order. However, Woolf’s writing style emphasizes a belief that time in fiction shouldn’t be chronological; instead, it should mirror how our minds often experience time and memory.

In real life, time feels elastic, moments stretch and contract, the past influences the present, and memories and sensations co-exist.

In her 1919 Essay titled “Modern Fiction,” Wolf distinguishes between External “Clock” time and Internal “psychological” time.

External Clock Time: Measured by hours, days, and years. Objective and linear.

Internal Psychological Time: Measured by feelings, thoughts, and memory. subjective and fluid.

Woolf emphasizes the belief that fiction should reflect how people actually live in time, not just simply how they experience time.

In Modern Fiction, Woolf writes:

“Examine for a moment an ordinary mind on an ordinary day. The mind receives a myriad impressions — trivial, fantastic, evanescent, or engraved with the sharpness of steel. From all sides they come, an incessant shower of innumerable atoms; and as they fall, as they shape themselves into the life of Monday or Tuesday, the accent falls differently from of old; the moment of importance came not here but there. If a writer were a free man and not a slave, if he could write what he chose, not what he must, if he could base his work upon his own feeling and not upon convention, there would be no plot, no comedy, no tragedy, no love interest or catastrophe in the accepted style, and perhaps not a single button sewn on as the Bond Street tailors would have it. Life is not a series of gig lamps symmetrically arranged; life is a luminous halo, a semi-transparent envelope surrounding us from the beginning of consciousness to the end. Is it not the task of the novelist to convey this varying, this unknown and uncircumscribed spirit, whatever aberration or complexity it may display, with as little mixture of the alien and external as possible?”- Virginia Woolf, “Modern Fiction” (1919)

4. Allow Your Writing To Be Lyrical And Symbolic:

One of the signature qualities of Woolf’s writing that distinguishes her from other Modernist and Stream of Consciousness writers is her lyrical and symbolic prose. Woolf wrote her novels as a poet would write a poem; her prose possesses a poetic quality rarely found in prose fiction.

She combines both rhythm and imagery to express emotion and consciousness within her characters. She employs symbolism through objects and motifs that often carry spiritual or psychological meanings beyond their literal senses. Rather than focusing on plot and dialouge alone, Woolf uses language as her expressive medium.

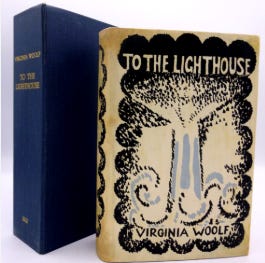

For example, read this excerpt from To The Lighthouse (1927).

“What is the meaning of life? That was all—a simple question; one that tended to close in on one with years. The great revelation had never come. The great revelation perhaps never did come. Instead, there were little daily miracles, illuminations, matches struck unexpectedly in the dark.” - Virginia Woolf (To The Lighthouse.)

The repetition of “The great revelation” and the imagery of “matches struck unexpectedly in the dark” create both rhythm and resonance. While objects such as the lighthouse and the sea act as prevailing symbols throughout the novel

Sea = change, continutiy, the unconcious, rhythm of life.

The Lighthouse = Aspiration, truth, permeance.

5. Everyday Life As Inspiration:

Fantasy, sci-fi, and historical fiction are all fun to write and read; however, writing and reading stories that focus on everyday life can be just as rewarding and entertaining. Woolf understood this, and she used everyday life as a key inspiration for her stories.

Ordinary moments of everyday life, such as walking to buy flowers, are not viewed as trivial occurrences in Woolf’s fiction; instead, they are actual material and catalysts of growth and change for her characters.

In Modern Fiction (1919), Woolf writes:

“The proper stuff of fiction does not exist; everything is the proper stuff of fiction—every feeling, every thought; every quality of brain and spirit is drawn upon; no perception comes amiss. But there is no reason to think that, because the proper stuff of fiction is not something different from life, it is therefore inferior in kind or in interest. The proper stuff of fiction is a little other than custom would have us believe it. It is the life of Monday or Tuesday. It is not necessarily what happens in real life that matters, but the way it is experienced.”

Implementing this approach of writing not only makes for better stories but also a more present and enhanced way of living when we treat even the mundane as artistic inspiration.

Virginia Woolf teaches us that there is poetry in the commonplace.

Conclusion:

When we read Virginia Woolf's works, we begin to realize that the smallest gestures and passing thoughts carry an entire universe of meaning. She mastered the art of consciousness by holding a mirror up to the external world, transforming fiction by rejecting the ordinary, outdated writing styles of her time.

One key lesson we can take from Virginia Woolf’s writing techniques is to break the rules. Too often, the writing process is bogged down by tedious grammar and stylistic rules, turning what should be a creative and personal endeavor into a structured, bland chore. When we read masterpieces such as Mrs. Dalloway and To the Lighthouse, we are inspired to believe that both writing and living are less about surrendering to the order and structure of life and more about surrendering to the flow and chaos of it.

Sources:

Woolf, Virginia. Modern Fiction. 1919. In The Common Reader, Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1925.

Woolf, Virginia. Mrs. Dalloway. Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1925.

Woolf, Virginia. To the Lighthouse. Harcourt, Brace and Company, 1927.

“Virginia Woolf.” Wikipedia: The Free Encyclopedia, Wikimedia Foundation, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Virginia_Woolf

Beautifully written.

Thank you! It was useful and inspiring!